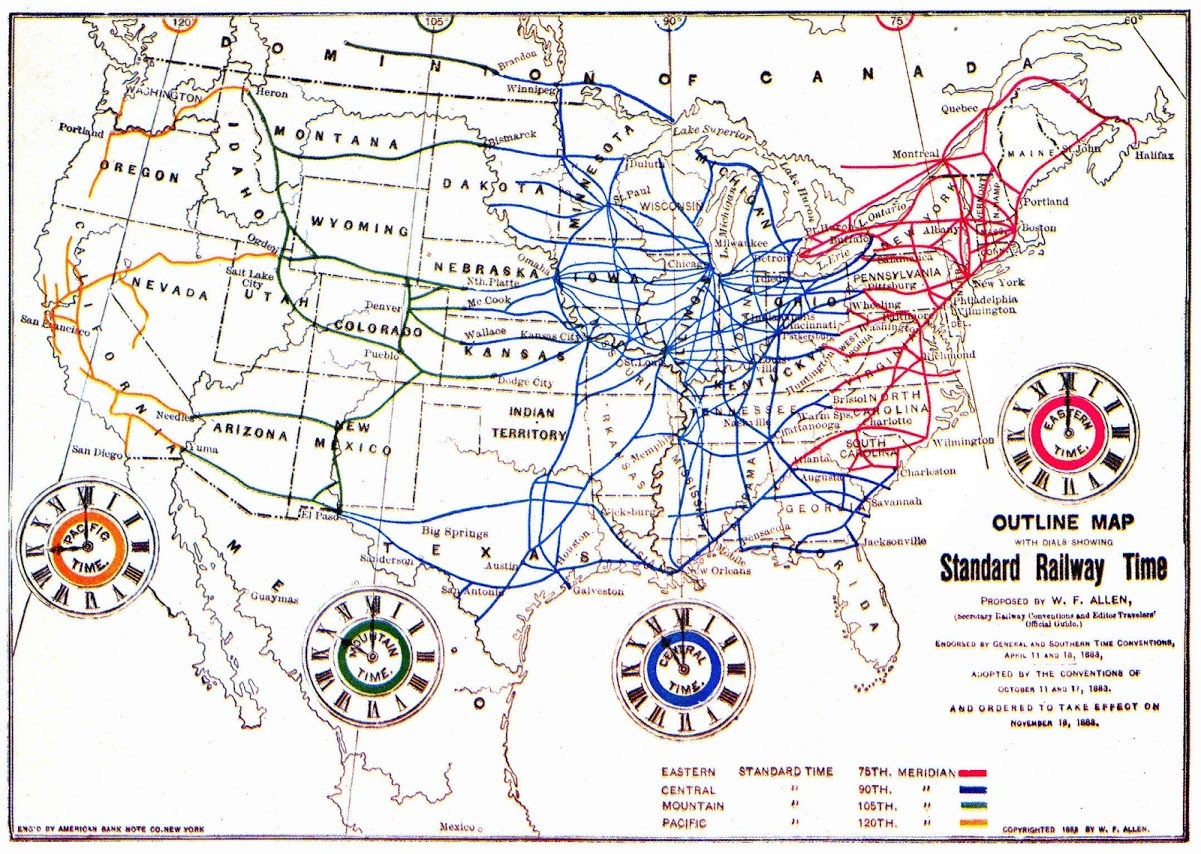

Map featuring William F. Allen’s proposal in 1883 for the introduction of Standard Railway Time. The clocks show the time which the railways of the same color on the map should adopt. The person responsible for implementing Standard Railway Time was William F. Allen (1846-1915), an engineer by training and editor of the Travelers Official Railway Guide for the United States and Cana-da. Allen was also secretary of the General Time Convention and The Southern Railway Time Convention, groups of railway managers and superintendents that met twice a year to discuss connecting train schedules. Image courtesy Railroad History published by the Railway and Locomotive Historical Society.

With the autumn season upon us, thoughts of shorter days and cooler nights come to mind. In November each year, we turn our timekeeping devices back one hour in observance of Daylight Saving Time. Origins of this practice are found in the railroad system and the standardized time zones implemented for train schedules. While the practice of Daylight Saving Time is relatively new, the idea is certainly not. One of America’s founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, suggested the idea in an April 1784 essay entitled, “An Economical Project for Diminishing the Cost of Light.” Franklin noted fuel expenses as they related to the nightlife in Paris, France; he proposed the time adjustment so individuals and businesses could take advantage of natural daylight in the evening and save on the cost of candle wax.

More than a century later, Franklin’s idea came to fruition in most of Europe as countries adopted Daylight Saving Time to conserve fuel used to produce electricity. Germany was the first to introduce Sommerzeit; in an attempt to alleviate hardships from coal shortages and air raid blackouts during World War I. In 1918, a similar law was enacted in The United States. Known as the Standard Time Act, it required the country to be split into four time zones (with two more zones added later when other states were accepted into the Union), each an hour in width: Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific (Alaska and Hawaii Aleutian) Standard or Daylight Time. The law also required daylight savings to be practiced for seven months in 1918 and 1919.

Contrary to public thought, farmers and agricultural associations lobbied against daylight savings time; the cow that is accustomed to being milked at 5:00 A.M. does not know any differently when the clock says it is 4:00 A.M. It also negatively impact-ed laborers who worked from seven o’clock in the morning until sundown. Proving to be unpopular among the public, most especially with farmers, the law was repealed in 1919. However, regions could choose to remain in the program if they preferred. From 1946 to 1966, there were no federal laws regarding Daylight Saving Time. Regions around the country still practiced their own form of local time.

At the advent of growing industrialization in the 19th century, steamships and trains required a form of time standardization. Nearly every major city in the United States used a different time standard, with more than three hundred local times from which to choose. This was understandably confusing for travelers. Railroad companies tried to combat this by creating one hundred railroad time zones, but this proved to only be a partial solution. In rapid succession, many states and cities passed ordinances or laws to adopt Standard Railway Time.

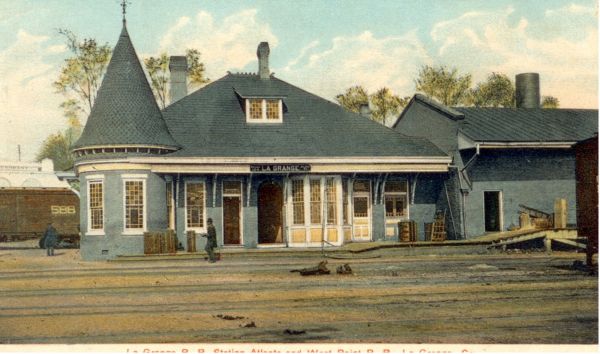

Standard Railway Time was important to any community with a depot and this area was no different. Troup County was deeply impacted by the railroad’s entry to the area in 1851. Gaining the nickname, “the great iron highway,” it created new economic markets in West Georgia, provided transportation for local citizens and encouraged the development of businesses. Notable railway companies that once traversed through Troup County include: The Montgomery & West Point Railroad, The Atlanta and LaGrange Railroad, and The Atlanta and West Point Railroad. Trains were important to local industry, textile production, and travel. Troup County fell into the Central zone of Standard Railway Time, implemented in 1883.

This postcard dated 1919, shows the Atlan-ta-West Point Railroad Depot in LaGrange. TCA Collections.

A standardization of time again became important to local citizens in the 1930s. Petitions to local mill executives, the mayor, and city council members to move the clocks one hour in the summer began circulating in LaGrange in 1932. According to the LaGrange Daily News, sponsors of the petitions cited more time for outdoor recreation, heavier traffic to local businesses, and having an additional hour for working in vegetable gardens as benefits of adopting Daylight Saving Time. As quickly as 1935, that same paper was reporting a change in favor. Local citizens voted in a special election on April 3rd of that year to not move their clocks forward an hour, which put local time an hour behind that of Atlanta.

In 1966, Congress reconciled this by passing the Uniform Time Act, requiring Daylight Savings Time to be implemented between the last Sunday of April and the last Sunday of October. Following the Federal Government, most of the country adapted their timekeeping in accordance with Daylight Saving Time, but Georgia did not implement the rule until 1970.

The “great iron highway” revitalized the nation’s economy and revolutionized means of travel; this was not lost on Troup County. Railroads changed the way we keep time and are a chapter in the history of Daylight Saving Time. No longer will a conductor shout, “all aboard!” from an Atlanta and West Point Railroad car and gone are the days when local time existed. But so as the ticking clock of history is marred with change, it is also enhanced with fascinating stories of progress and improvement. – Katie Still