LaGrange Daily News article clipping discusses the deer population in Troup County

It’s autumn, and our woodlands are resplendent with yellow, gold, and red – and fluorescent orange. Yes, it’s deer season. The people of our region have sustained a long and complex relationship with Odocoileus virginianus, the white-tailed deer. Long before European settlers arrived in the area that now includes Troup County, deer were a mainstay in the diets of the people who occupied this land. At the end of the last ice age, large herbivores like bison and elk began to disappear from southern North America. (A few bison persisted in Georgia into the eighteenth century.) Some attribute their de-mise to the warmer climate; others suggest that overhunting by native people was the cause. The smaller graceful whitetails filled the niche, and thrived anywhere that breaks in the forest canopy allowed the growth of understory plants on which they fed. Native people learned to use fire as a tool to promote open woodlands which the deer preferred. As people made the slow transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture they continued to use fire to change the landscape. The popular notion is that European settlers encountered an impenetrable virgin forest, but in reality, the landscape they found was already significantly altered by humans.

Buckskin breeches were made of both male and female deer and were both very comfortable and durable. Courtesy Metro-politan Museum of Art.

Much of Canada and the western U.S. was explored in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, by trappers seeking beaver pelts to fill the demand for fashionable hats. The deerskin trade played a similar significant role in the history of the Southeast. The Augusta-based Brown, Rae and Company dominated the deerskin trade as the Hudson Bay Company monopolized the beaver trade. Traders working for Brown and Rae ventured into the interior over an ever expanding network of trails to do business with the natives. Deer hides were the currency for European trade goods, and events back in Europe created high demand. Between 1710 and 1720 disease killed nearly half the cattle on the European continent. Fearing spread of the disease, England banned importation of cattle and hides from Europe. Colonial traders stepped into the void. Extant records from the period tell us that between 1699 and 1715, more than fifty thousand deer hides were shipped from Charleston each year. Researchers have estimated that between 1739 and 1761, 1,250,000 deer were killed to supply the trade.

The deerskin trade profoundly affected Native American culture. European diseases had already devastated native populations. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, growing dependence on European manufactured goods adulterated their culture. Competition for the dwindling deer resource led to territorial disputes and enflamed long-standing rivalries among native groups. As Europeans established a firm foothold along the coast, there was tremendous upheaval in the hinterland. Weaker factions were absorbed into more dominant groups, or simply died out. In our region a loose amalgamation that became known as the Creeks emerged as the dominant group. The hardy traders, often Scottish, entered this perilous world leading pack horses, laden with trade goods, along well-established trails. The Okfuskee Trail was the primary route through what would become Troup County. The traders, whose Scottish homeland was dominated by a system of clans and chiefdoms remarkably similar to that of the Creeks easily adapted to native culture. They intermarried and their offspring rose to prominence, frequently instigating and dominating negotiations that ceded Indian land to the Whites.

Image of Troup County in the autumn. Courtesy Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

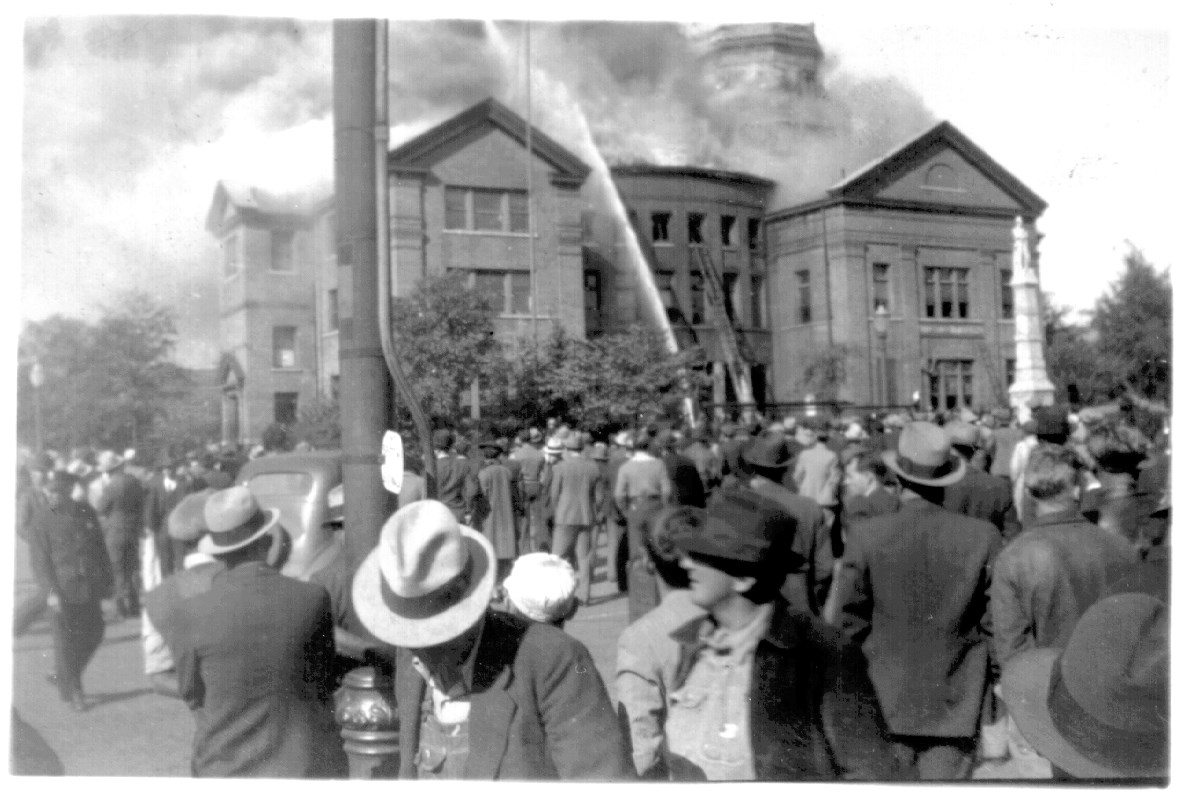

Settlers who arrived in the newly formed county of Troup in the late 1820s found a healthy deer population. Clifford Smith, in his 1933, History of Troup County, recounts: According to John T. Rutledge, who spent his boyhood days in this community, one of the interesting divertissements of the time was that of deer hunting. The hunters started the dogs in the Tanyard branch swamp (junction of Hill and Greenville Streets) and the dogs pursued the deer across the present Court Square towards the McLendon branch north of town and then on towards Yellow Jacket Creek, the hunters shooting them from various stands. One of these stands was situated at the southwest corner of the square. That first generation of Troup Countians would be the last to engage in the sport of deer hunting for well over a century. Indiscriminate hunting contributed to a rapid decline in the deer population, but habitat destruction, clearing the forest for agriculture, was the real reason that deer disappeared from Troup County. Writing from a Confederate army camp on June 20, 1861, John Thomas Traylor told his wife back in Troup County’s Long Cane Community, “Tell Pa that Bill Hulbert said today that he always loves to eat at his house to get venison. I hope we all get back home safe, then we can go up to Randolph [Randolph County, Alabama] and get some venison, though I guess we will stay home a while before we go out on a hunting expedition.” We can infer from Traylor’s letter that by 1861, there were few, if any, deer to hunt in Troup.

Image of Troup County in the autumn. Courtesy Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Onset of the boll weevil, and other factors, sig-naled the end of the South’s cotton economy. People abandoned their farms for city life. By the mid-twentieth century, Troup County’s dominant habitat was pine for-est rather than farm fields. The farmland and abandoned fields were ideal habitat for small game. The first half of the twentieth century was the heyday for rabbit hunters and bird hunters, but the changing habitat brought a decline in small game. Local sportsmen began to look for alternative species to hunt. Beginning in 1927, Forest Ranger Arthur Woody successfully released hand-reared fawns in the Chattahoochee National Forest in north Georgia. Woody’s success led the Georgia Game and Fish Commission to undertake restocking projects throughout the state, beginning around 1948. A front-page story in the LaGrange Daily News for January 8, 1962, declared that Troup County hunters would be able to hunt deer in their home county in five years. With backing from the Troup County Sportsman Club, twenty whitetails, imported from Wisconsin, were re-leased at the old Garrett farm near Liberty Hill. A subsequent release of deer from Texas took place near Salem Community. The restocking program exceeded all expectations, often with unforeseen and unwanted consequences. Georgia’s deer population peaked in 1998 at about 1.4 million. Today the herd is estimated at one million. – Randall Allen