“There’s an app for that.”

Does that statement intimidate you? Probably not, if you are a millennial or younger. If your timeline is a lengthy one; if you remember where you were when Kennedy was assassinated; if you still write checks using cursive style, then digitization and the Ethernet might be a bit overwhelming.

A recent donation to the Historical Society’s Legacy Museum caused us to reflect on the phenomenal pace of change in written communication and records keeping. When Mr. Ed Kaplan closed his clothing store, he donated a small printing press he had used to create posters and other advertising. Under the guise of preparing a Hands On History segment our staff enjoyed tinkering with the press. We learned, among other things, that the printed image is reversed. It’s quite tricky to set each letter upside down and backwards. More importantly, after enduring several days of red-tipped fingers we realized that we must find a water-soluble substitute for the indelible ink that came with the press.

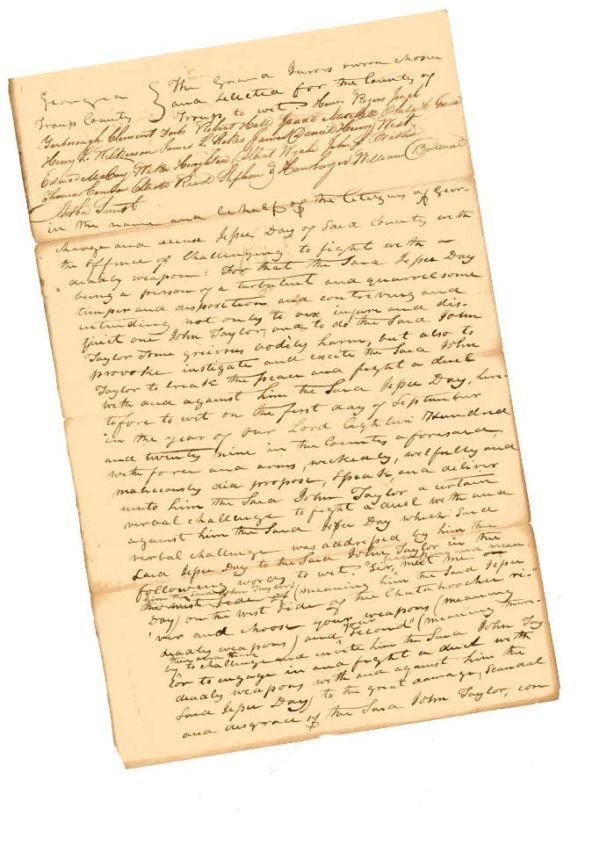

Troup County Superior Court document detailing the case of John R. Thom-as for horse stealing was heard in September of 1825. TCA Collections.

Our effort to learn more about the printing process emphasized just how easy it has become to collect and disseminate information. A simple Google search provided us with all sorts of facts about block printing techniques in ancient Korea and China. We learned that Johannes Gutenberg, famous for printing the Bible in 1455, was sued and lost his press to his creditor, Johann Fust. Fust and his partner, Peter Schoeffer, are credited with the first typo, in 1457, when they printed “spalm” instead of “psalm.”

Documents housed at Troup County Archives reflect the changes in record-keeping technology that have occurred in the two centuries since our county was founded. It is only in recent years that the changes have accelerated so dramatically. Until the advent of the typewriter in the late nineteenth century, much depended on the skill and attentiveness of the court clerk. We can visualize a clerk of the 1820s, quill in hand, seated on a hard bench meticulously transcribing cases. John R. Thomas’s case for horse stealing is a good example.

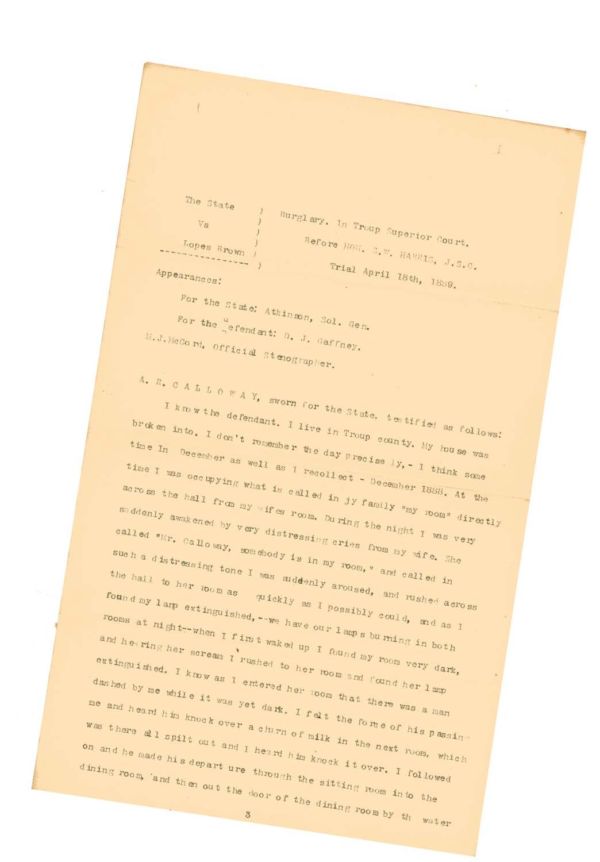

One of the earliest known trials to be recorded by a stenographer in Troup County is this one, The State of Georgia vs. Lopes Brown from April 18, 1889.

Note that the grand jurors’ names are in a different hand and different ink, indicating that the clerk, N. Johnson, probably prepared the indictment in advance. To the practiced eye Mr. Johnson’s handwriting is not difficult to read. That isn’t always the case. As we attempt to decipher documents we often wonder just how some clerks with such abysmal handwriting managed to keep their jobs.

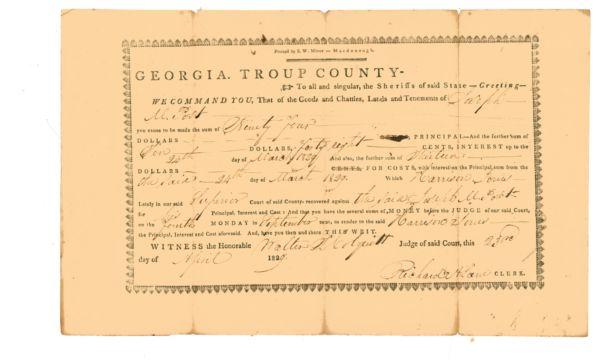

Preprinted forms, though expensive, were used for routine records such as this 1829 FiFa. Note that it was printed by S.W. Minor of Macdonough, Georgia. We rarely find the printer’s name on a form, so we don’t know when court documents were first produced locally. County Historian, Clark Johnson, suggests that it was probably around 1843, when the LaGrange Herald, our first newspaper, began publication. By the 1870s, the LaGrange Reporter Printing Office supplied local courts with pre-printed legal documents.

M.J. McCord, Official Stenographer, from Atlanta, produced our first typewritten court document, a transcript of the burglary trial of Lopes Brown on April 18, 1889. At that point, the typewriter had been around for fifteen years but it was slow to gain popularity locally. It was well into the twentieth century before the typewriter replaced longhand as the preferred method for preparing court documents.

Now we bemoan the fact that many schools no longer teach cursive writing. We worry that future archivists will find documents written in longhand as puzzling as hieroglyphics. Oh, wait, there’s an app for that. It’s

called Pen to Print, and it translates handwriting to block print.

— Randal Allen

This preprinted FIFA document was filed on April 23, 1892. TCA Collections.

.