By Randall Allen

The proprietors of Brown Brothers’ Machine Shop in New Castle, Pennsylvania, made a gruesome discovery when they opened their office on the morning of December 29, 1894. Their patent attorney, William Huntley, sat slumped at his desk, lifeless eyes staring through his thick wire rimmed glasses. An empty laudanum bottle sat nearby. The Browns telegraphed Huntley’s son in LaGrange, Georgia, informing him of his father’s demise. They received a startling reply. Mr. Huntley’s family had neither the resources nor the inclination to bring the body home to LaGrange. William Hutchinson Huntley was buried in a pauper’s grave in New Castle’s Greenwood Cemetery. Fifteen years later, Union veterans who were aware of Huntley’s service in the Confederate army, marked his grave. (1) After Mrs. Huntley died in 1901, the family erected a marble obelisk in the Huntley family plot in LaGrange’s Hillview Cemetery. One side is inscribed, “In memory of William H. Huntley, beloved husband of Martha Park Huntley. He was a true and dependable gentleman.” The man that no one claimed has monuments in two cemeteries, fitting irony for such an enigmatic character.

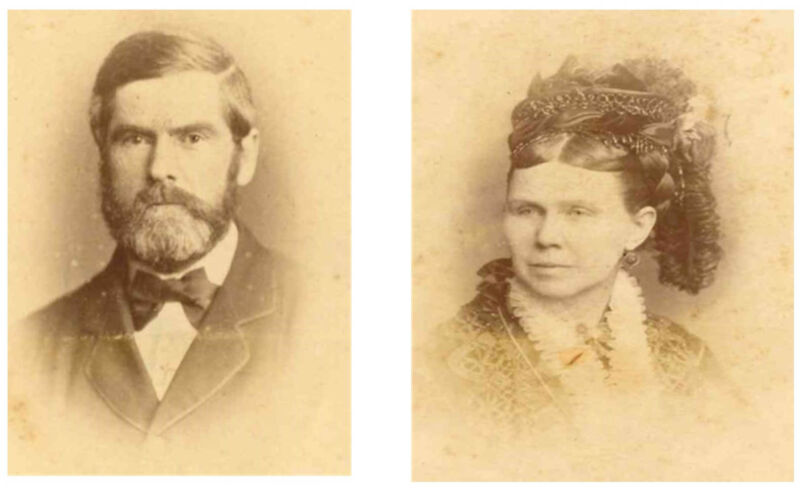

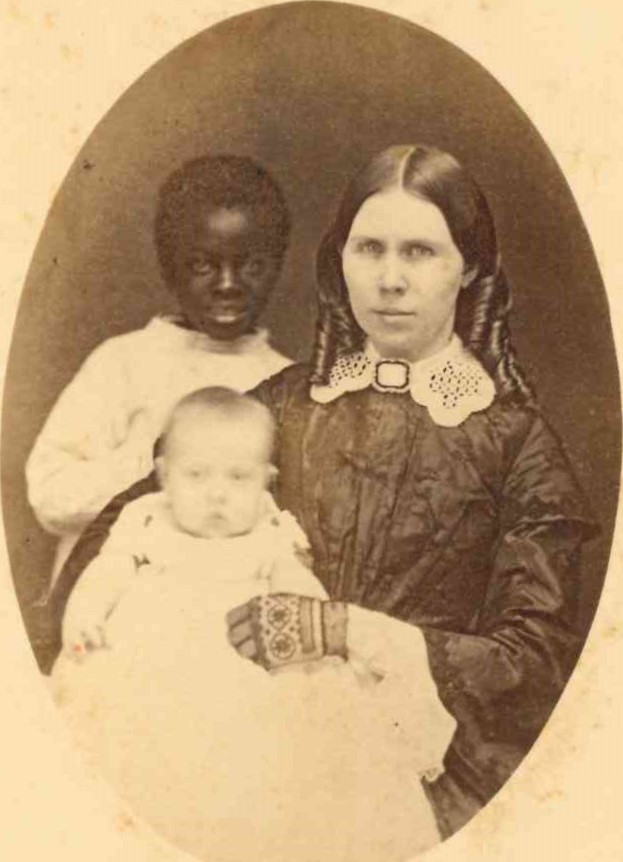

William H. Huntley and his wife, Martha, were photographed by the Southwell Brothers of London when they toured Europe with their children in 1876. (Troup County Archives)

He was born near Syracuse in Onondago County, New York, on September 14, 1827, the son of Heman and Rebecca Forman Huntley. On February 5, 1852, at Greenville in Meriweather County, Georgia, he married Martha Caroline Park. We know nothing of his early years or what prompted him to migrate south. His father was employed manufacturing salt from Onondago County’s brine springs. Perhaps the young man headed south to avoid working in the salt vats. His brother, Asahel Huntley, went to the California gold fields. Martha’s parents were John and Sarah Robertson Park. John Park was affiliated with LaGrange Female Institute (LaGrange College) in its early years, and at the time of his death in 1849, he headed a school in Greenville. Education was a priority in both the Park and Huntley families. William Huntley spared no expense in providing for his family, even to the point of overextending. Huntley sold carriages and buggies in Greenville and West Point before he settled in LaGrange in the summer of 1856. The 1860 census reveals that he and Martha had two young sons, John Park and William Henry. A daughter, Mary Louise, came along in 1864. Through most of his life, Huntley maintained a conspicuous profile in both business and civic affairs that sometimes bordered on flamboyant, but he kept one aspect of his career a closely guarded secret.

When Civil War came, Huntley enlisted in the LaGrange Light Guards which became Company B, 4th Georgia Infantry Regiment. At thirty-four, he was older than most recruits, and he was handicapped by poor eyesight, but as a staunch proponent of Southern rights he was impelled to join. During the first year of war, the Fourth Georgia guarded the vital naval yards around Norfolk, Virginia. Huntley, with the rank of Second Sergeant, functioned as company clerk. He kept folks back in LaGrange informed about the Light Guards’ activities through a regular correspondence with the LaGrange Reporter. The regiment transferred to field duty in April, 1862, and it became apparent that Huntley’s poor eyesight made him unfit for active campaigning. He was discharged on May 3, 1862, and returned to LaGrange. Through the remainder of 1862, and 1863, he engaged in business, buying and selling property around LaGrange. He was elected Justice of the Peace in February, 1863, and in August he enlisted in the Chattahoochee Rangers, Company H, 2nd Georgia Cavalry State Guards, a unit raised for six month’s service within the state of Georgia. On December 8, 1863, Huntley recorded a deed by which he sold a house and lot on Depot Street in LaGrange. After that, his name disappears from public records of LaGrange and Troup County, until March 26, 1869, when he advertised in the Reporter that he was once again engaged in the sale of carriages. His whereabouts and activities in the intervening years constitute a murky tale of intrigue and adventure.

Huntley left no memoir of his exploits. If he ever divulged his role as a secret agent to his family or fellow veterans, they chose not to talk about it after his death. What little we know comes from memoirs of other agents, and from transcripts of trials heard in Canadian courts. (2) On October 19, 1864, Huntley participated in the audacious Confederate raid on the town of St. Albans, Vermont. In a military sense, the raid was insignificant. Only about twenty Confederate soldiers participated, but their mission had tremendous psychological impact on New Englanders and it further complicated already strained relations between the United States and Canada and Great Britain. (3)

Huntley served as commissary captain while he was affiliated with the state guard cavalry unit. In that capacity, he traveled widely procuring supplies. In court testimony Huntley claimed that in December 1862, he was “robbed by the Yankee vandals of property valued at over $50,000,” (4) suggesting that he was engaged in the lucrative but highly risky business of running commodities through the blockade. A passport issued to Huntley in January 1864, and signed by Secretary of War, James A. Seddon, and Secretary of State, Judah P. Benjamin, authorized him to travel freely throughout the Confederacy. The implication is that he was a courier for Confederate authorities. In February, he was in Wilmington, North Carolina, the primary base for blockade runners. Around the first of June, he was in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the company of another agent named Bennett H. Young. (5)

Bennett Young, was a twenty-one-year-old Kentuckian, veteran of John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry, and escapee from a Federal prisoner of war camp. Young made a harrowing run through the blockade in order to confer with Confederate authorities at Richmond regarding his proposal to free Confederate prisoners held at Chicago’s Camp Douglas. Young had previously escaped from Camp Douglas and made his way to Canada. After several months living among Confederate expatriates in Canada, he sailed from Nova Scotia to Bermuda, where he boarded a blockade runner bound for Wilmington. We don’t know any details about how Huntley and Young became compatriots, but by early summer 1864, they were back in Canada, reporting to Confederate commissioner, Clement C. Clay. From his base in Canada, Clay and other agents, coordinated a number of enterprises, including efforts to disrupt shipping on the Great Lakes, arson in New York City, and a plot to spread yellow fever in northern cities, all intended to disrupt the United States’ war effort. (6)

Confederate authorities in Richmond indorsed Young’s plan, gave him a lieutenant’s commission, and sent him back to Canada to work with Clay.

Confederate States of America, War Department, Richmond, Virginia, June 16, 1864

To Lieut. Bennett H. Young:

Lt: You have been appointed temporarily, lieutenant in the Provisional Army for special service. You will proceed without delay to the route already indicated to you, and report to C.C. Clay, Jr. for orders. You will collect together such Confederate soldiers who have escaped from the enemy, not exceeding twenty in number, as you may deem suitable for that purpose, and execute such enterprises as may be indicated to you. You will take care to organize within the territory of the enemy, to violate none of the neutrality laws, and obey implicitly these instructions. You and your men will receive transportation and customary rations, and clothing or commutation thereof.

James A. Seddon, Secretary of War (7)

Young’s plan to liberate Camp Douglas was but one element in a much larger plot known as the Northwest Conspiracy. Confederate officials hoped to motivate the anti-war faction of Northerners, the so called Copperheads, to oust the Lincoln administration by any means necessary. Another Kentuckian, Captain Thomas Henry Hines, was in overall command of the Chicago expedition. The action was scheduled for late August when the Democrat Party would hold their national convention at Chicago. As approximately seventy agents, including Huntley, rendezvoused in Chicago, it became apparent to Hines and Young that the plot was too cumbersome and required impossible coordination among the various factions. They aborted the mission, but Young immediately set about organizing a backup plan, one that he would tightly control. A month later, Young and his recruits were back in Canada, where they received Clay’s approval for a new mission.

Your report of your doings under your instructions of the 16th June last, from the Secretary of War, covering the list of the twenty Confederate soldiers who are escaped prisoners, collected and enrolled by you under the instructions, is received. Your suggestions for a raid upon the most accessible towns in Vermont, commencing with St. Albans, is approved, and you are authorized and required to act in conformity with the suggestion.

C.C. Clay, Jr. Commissioner, C.S.A.

October 6, 1864 (8)

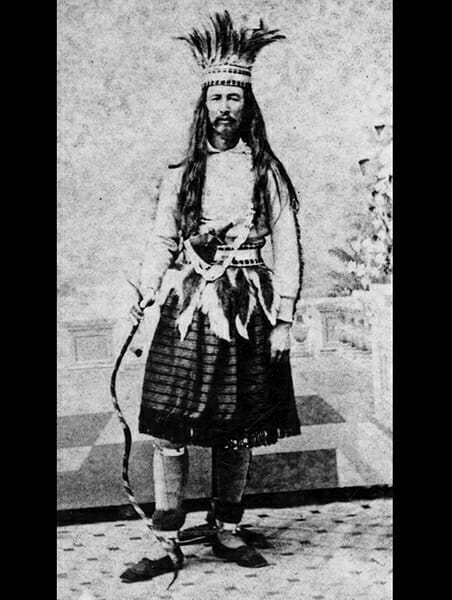

Young called his volunteers the 5th Company, C.S.A. Retributors. William H. Huntley is the third name on Young’s roster, indicating that he was third in command, behind Young and Thomas B. Collins, formerly a captain in the 7th Kentucky Cavalry. Huntley’s age and background distinguished him from the other Retributors. He was one of only two over thirty years old, and almost all the other raiders were veterans of John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry. Young’s notes appended to the roster support the theory that Huntley functioned as a covert courier:

Wm. Hutchinson Huntley, now called by Wm. Hutchinson, formerly of Company B, 4th Georgia Infantry, and late of Company H, 2nd Georgia Cavalry, and acting commissary captain under Col. Wilcoxon and Gen. Iverson. Is here by order on special business. Another may take his place. (9)

On October 10, 1864, Young and two companions checked into the Tremont House Hotel in St. Albans, Vermont. Over the next week at least fifteen more men arrived in town, all purporting to be on business or hunting trips. Huntley, who was registered at a St. Johns, Quebec, hotel as W.P. Jones, traveled by train to St. Albans on October 18th. (10) They attracted little attention in the town of four thousand residents. St. Albans was a transportation hub, only fifteen miles from the Canadian border. It boasted a foundry and machine shops for the Central Vermont Railway, but the raiders were more interested in the town’s substantial banks. (11) The raid was initially scheduled for October 18th, but when the raiders learned that it was market day and town would be crowded with local farmers, they postponed it a day.

Wednesday, October 19th, was cool and overcast. As the town clock struck three, Young sauntered in front of the American House Hotel and announced that he was taking possession of the town in the name of the Confederate States of America. Bystanders thought that he was joking until a few gunshots erupted, and several of the young strangers unleashed an unnerving chorus of high pitched yells. One raider herded bystanders onto the town green while others undertook the important task of rounding up horses. Three detachments simultaneously concentrated on the town’s banks. Thomas Collins led three other raiders into the St. Albans Bank where they forced the tellers to swear allegiance to the Confederacy before taking about $80,000. Four more raiders targeted the First National Bank of St. Albans. William Huntley led a group to the Franklin County Bank. Huntley entered ahead of his companions and nonchalantly inquired about the price of gold. After a brief conversation with the cashier and other customers Huntley pulled his revolver and demanded “greenbacks, bills, and notes of every description.” Bank customer, Jackson Clark, made a dash for the door but Huntley’s men forced him back as they entered. Huntley locked Clark and cashier Marcus Beardsley in the bank’s vault as his men stuffed cash into their satchels. A week later, when Beardsley identified raiders in their Montreal jail cell, he took the opportunity to chastise Huntley, telling him it was inhumane to lock him in the air-tight vault, to which Huntley replied that it was no worse treatment than Beardsley’s countrymen inflicted upon the Southern people. (12)

The whole thing was over in fifteen or twenty minutes. The raiders rode away with around $208,000 in banknotes and greenbacks. (13) One raider, Charles Higbee, received a serious wound in his shoulder, but recovered. Three civilians were wounded; one fatally. As they trotted out of town, the raiders randomly tossed four ounce bottles of the incendiary called Greek fire in an effort to burn the town, but the chemicals failed to ignite.

Young had intended to attack the nearby town of Swanton on the same day, but when he realized that a large posse from St. Albans were pursuing, he ordered his raiders to head to the Canadian border. Young remained behind to tend to Higbee, who by that time, was unable to travel farther. (14) The outraged Vermonters followed the raiders into Canada. Canadian authorities were alerted by telegraph to be on the lookout for suspicious strangers, and within twenty-four hours most of the raiders were apprehended. Huntley eluded authorities until October 24th, when he was arrested near Montreal, the last of fourteen raiders captured. (15) Authorities recovered nearly $87,000 of the stolen money. The raiders were held briefly at St. John’s, then sent to Montreal to await an extradition hearing. In Montreal, Southern refugees and sympathizers hailed them as heroes. Back in Richmond, Confederate authorities followed the raiders’ progress. On October 25th Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin noted tersely in his diary, “Fourteen of the St. Albans raiders had been captured.” Clement Clay hired a team of lawyers to represent the raiders in Canadian courts.

Local Canadian constables and magistrates cooperated with the Vermonters in rounding up the raiders, but they refused to allow the Americans to take the prisoners back to Vermont. Provincial authorities were incensed that Americans had violated Canada’s sovereignty in pursuing the raiders. The Southerners quickly realized that animosity between the New Englanders and Canadians regarding the border and sovereignty could be used to their advantage.

Bank cashier Marcus Beardsley identified Huntley as one of the robbers, stating that he recognized him even though Huntley had shaved his whiskers and was now wearing thick spectacles. Canadian authorities stated that when arrested Huntley had in his possession two loaded revolvers and $10,000 in Franklin County Bank notes. (16) Huntley, still calling himself William H. Hutchinson, made a statement to the court.

I am a native of the State of Georgia, and a citizen of the Confederate States of America. I have been an officer in the Confederate army since April, 1861. I am not guilty of the charge brought against me. I owe no allegiance to the Yankee government. In December, 1862, I was robbed by the Yankee vandals of property valued at over $50,000. I have not violated the laws of Canada or Great Britain. I am perfectly willing to share the fate of my countrymen and fellow soldiers.

William H. Hutchinson (17)

On December 13th Judge Charles J. Coursol ruled that the extradition treaty between the United States and Canada stipulated that only a warrant signed by the Governor General of Canada was valid in extradition cases. Since the warrants used to arrest the raiders had all been issued by local magistrates, the extradition treaty did not apply. He concluded that his court had no jurisdiction and released the raiders. Adding insult to injury, he turned over the confiscated money to Confederate bankers in Montreal. The prosecutors were dumbfounded but immediately sought proper warrants. Huntley, Young, Charles Swagar, Marcus Spurr, and Squire Tevis were rearrested, but the other raiders disappeared and Canadian authorities made only a half-hearted effort to find them. The second trial began on December 27th and the case proceeded sluggishly through the Canadian court for months. It hinged on whether the raiders were legitimate Confederate soldiers or simply a band of bank robbers. Evidence presented in the second trial helps us trace Huntley’s peregrinations as a secret agent.

Huntley offered justification for the raid in his statement to the court at the second trial.

I am a native of the State of Georgia and owe no allegiance to what was at one time the United States; I am not guilty of any of the charges brought against me here; In April, 1861, I joined the Southern army, and have been connected with it up to the present time; I have violated no laws of Canada or Great Britain; For the first four years of this present unhappy war the Southern people were only doing their duty repelling an insolent foe and protecting themselves against outrage, injury, and insult; They fought against heavy odds as the muscular resources of the combined world were arrayed against them, and they have overcome great difficulties with the cheerfulness and spirit of a brave people; Our friends, neighbors, and relatives have been plundered, and in many instances murdered, and it is the bounden duty of every Southern man to protect and avenge them in an individual or national capacity; No civilized people could do more and no true patriot, of whatever clime, could do less. (18)

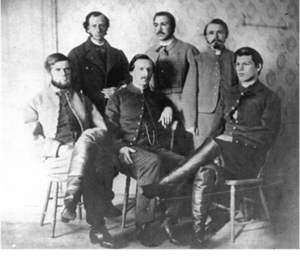

William Notman photographed the raiders on the steps of the Montreal Jail on December 27, 1864, as their second trial began. Pictured are: Marcus A. Spurr, Charles M. Swagar, William H. Huntley, George N. Sanders (ex-officio Confederate commissioner), Stephen F. Cameron (chaplain), Squire T. Tevis, and Bennett H. Young.

(William Notman Photographic Collection, McCord Museum, McGill University)

Attorneys for the five raiders based their defense on the presumption that they were soldiers acting on orders from the Confederate government. As evidence, they produced Bennett Young’s commission, William H. Huntley’s passport, and several messages exchanged between Young and Clay. Stephen Frick Cameron, a Confederate chaplain, made the arduous journey through Federal lines to Richmond to retrieve company rosters that verified each raider’s original enlistment in the Confederate army. Prosecutors questioned the authenticity of the documents and pointed out that the name on Huntley’s passport and enlistment papers was different from the one he gave when he was arrested. The court rejected their arguments, and in April 1865, ruled that the five raiders were legitimate soldiers engaged in an act of war. U.S. authorities attempted to have the raiders charged with violating Canada’s neutrality laws, but by October all charges were dropped.

This photograph of the raiders was made about mid-February, 1865. Standing: Stephen F. Cameron, Confederate chaplain who, disguised as a priest, smuggled valuable documents through Union lines; Charles M. Swagar, died in Paris in 1871, while observing the Franco-Prussian War; Squire T. Tevis, received a presidential pardon in April 1866, and returned to Kentucky. Seated: William H. Huntley, after exile in Europe, returned to LaGrange, Georgia, where he engaged in various businesses; Marcus A. Spurr, attended McGill University in Canada, married the daughter of a wealthy Nashville banker, and settled there; Bennett H. Young, leader of the raid. (St. Albans Historical Society)

Huntley and his cohorts were free; the war was over, but they couldn’t go home. They were excluded from the general amnesty issued to other Confederates. They attempted to make places for themselves in the large community of expatriate Southerners living in eastern Canada. Both Bennett Young and Marcus Spurr married Southern girls whose families were refugees in Canada, and evidence indicates that Huntley’s wife, Martha, and their three children joined him. The Southern community around Montreal soon began to break up, and within a few months, the Huntleys, Bennett Young and his bride, and Charles Swagar sailed to Europe. Marcus Spurr and Squire Tevis obtained presidential pardons and returned to Kentucky.

While in exile, Bennett Young attended Queen’s College in Ireland and Edinburgh University in Scotland. After two years, he returned to Canada to study law, and in 1868, he took his young family back to Kentucky, where he enjoyed a long career as an attorney and philanthropist. Charles Swagar joined an American banking firm in France. In November 1866, he was appointed U.S. Consul at St. Etiene, and served with distinction in spite of Washington officials’ misgivings about his past. Swagar eventually returned to Louisville, Kentucky, where he became a banker. The prospect of adventure lured him back to France during the Franco-Prussian War, and he was fatally wounded when his hotel was shelled during the 1871 siege of Paris. (19)

William Huntley’s exile in Europe is more difficult to trace. A portrait of Martha and her infant daughter, Mary Louise, made by British photographer, Edwin Mayall, proves that they were in London shortly after the war. How Huntley supported his family is a mystery, though it is likely that much of his wealth came from his wife’s family. No evidence has been located to indicate that Huntley ever received a pardon from the Federal Government, but by March, 1869, the Huntleys were back in Troup County. Family tradition indicates that, in later years, he declined to run for public office because he refused to sign an oath of allegiance to the United States. (20)

Martha Park Huntley and her daughter, Mary Louise (born October 3, 1864) were photographed by Edwin Mayall at his Regent Street studio in London in the latter part of 1865 or early 1866. The Black child in the photograph might be Sam (Kirby). On March 9, 1863, Huntley purchased from John T. Kirby a slave woman named Rachel and her son, Sam. They served as house servant and nurse for the Huntley children.

(Troup County Archives)

With typical vigor, Huntley pursued a number of business and civic ventures upon his return to LaGrange. On March 19, 1869, he advertised in the Reporter that he was selling Concord buggies, Studebaker wagons, and Challenge washing machines. He brokered the shipment of red cedar lumber to England. He bought real estate, including the site of the old Southern Female College and a five-hundred-acre plantation on Tin Bridge Road between LaGrange and Hogansville. In May, 1869, Huntley was elected to LaGrange City Council, and embarked on a street improvement project which he partially funded with his own money. Huntley aligned with C.H.C. Willingham, editor of the LaGrange Reporter, who was an outspoken critic of Georgia’s Reconstruction regime. When Huntley was invited to address his son’s LaGrange High School class in November 1869, he recited “I’m a Good Old Rebel,” a poem that bluntly expresses the sentiments of the unreconstructed Southerner. (21) Unafraid of risk or novelty, on January 9, 1871, Huntley acquired distribution rights in LaGrange for James Plimpton’s patented roller skates. The venture proved so successful that later that year, Huntley traveled to South America representing Plimpton, and credited himself with introducing roller skating to that continent. (22) Huntley’s expedition to South America reveals a pattern he was to follow for the remainder of his life. On the verge of success with one project, he took off on a new scheme, leaving loose ends to unravel. He was popular among Troup County Democrats, and a movement arose to draft him as a candidate for the legislature, but his departure for South America coupled with unanswered questions about his failure to sign the loyalty oath quashed any hope of a career in politics.

Huntley embarked on his boldest business venture when he became an incorporator of the North and South Railroad of Georgia. The company received its charter on October 24, 1870, with the intention to build a rail line between Columbus and Rome. Huntley served as secretary, traveled extensively, and worked tirelessly to solicit subscriptions. By 1874, about twenty miles of track were completed between Columbus and Hamilton. About that time, Huntley took his family on an extended (nearly three years) tour of Europe where he promoted roller skating and other ventures. Martha Huntley penned a series of letters to her brother, Howard Park, editor of the Sandersville, Georgia Herald, in which she described in vivid detail the family’s experiences, including an audience with the Pope. Upon his return from Europe in June 1877, Huntley found that revenue for the rail line fell far short of expectations. By 1878, the company declared bankruptcy. Huntley, to use the Victorian euphemism, was seriously financially embarrassed. His success in other endeavors was not enough to overcome his debts.

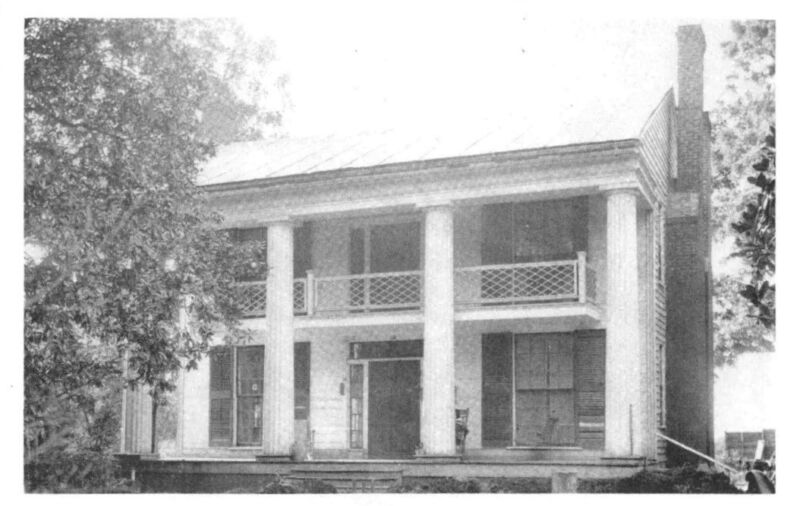

On July 20, 1874, Huntley purchased the old Thomas Greenwood house at the corner of Broad Street and North Greenwood Street in LaGrange and had the house renovated while his family toured Europe.

William H. Huntley paid J.A Spear $2,500 for this house located at the corner of Broad and Greenwood Streets in LaGrange. In a deed, recorded September 5, 1877, Huntley put the house in his wife’s name, thus saving it from creditors. The lot is now occupied by a bank, but magnolia trees that Huntley planted in 1883, still grace the site.

(Historic American Building Survey, Library of Congress)

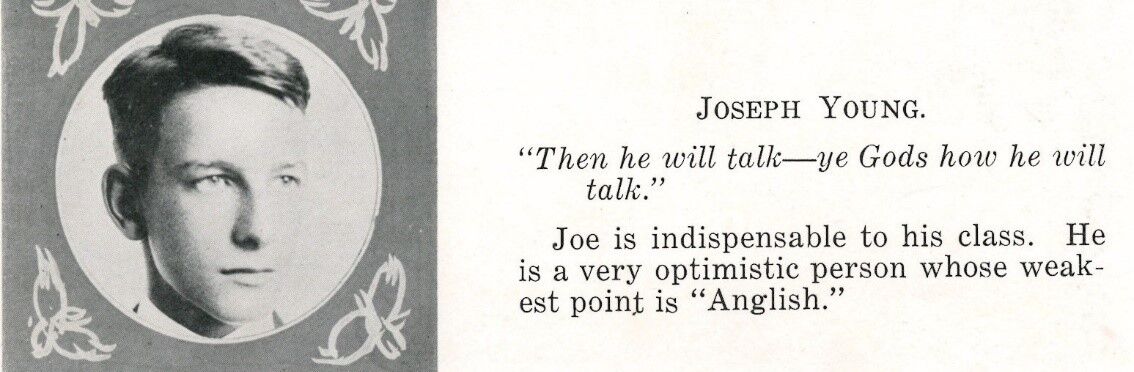

Huntley’s difficulties were not all financial in nature. By 1877, his son, Will, had graduated from Emory College and was co-principal of LaGrange High School. The city council, which in those days oversaw public education, failed to reappoint Will for the 1878 school term. Huntley, Sr. was incensed and blamed councilman Francis Marion Longley for the slight to his son. (23) Longley held the prestigious position of captain of the LaGrange Light Guards. (At the end of Reconstruction, the Light Guards had been reorganized as a paramilitary social organization.) Huntley proceeded to maneuver Longley out of the plumb post. After a drill session, from which Longley was absent, he treated the Guards to ice cream. A lemonade social soon followed, and Huntley even paid off an outstanding debt for some of the organization’s equipment. In September 1878, Huntley was elected captain, and the Guards flourished under his leadership. They won statewide drill competitions, and sponsored a series of grand soirees around LaGrange. Huntley’s success with the LaGrange Light Guards was his last hurrah.

As ever, he quickly moved on. Early in 1879, he returned to England on business, and remained there until October. On February 3, 1879, Huntley wrote to the Reporter from London.

I received a letter from home yesterday which contained a printed slip, cut from some newspaper, which reads as follows, “Capt. W.H. Huntley, of LaGrange, Georgia, has backed Dr. W.F. Carver for $10,000 against Capt. Bogardus, in a shooting match, to come off in New York City, in October, next.”

It appears that F.M. Longley, too, was capable of taking advantage of his rival’s absence. Huntley denied the claim and insisted that he was opposed to gambling of any kind. (24) Adam H. Bogardus and William F. “Doc” Carver were renowned marksmen, both touring England during Huntley’s time there.

The public feud with Longley was only part of Huntley’s mounting troubles. In April 1882, he was forced to sell the Southern Female College tract. When Huntley’s father died in February 1884, he returned to New York to claim his share of the estate but he was rebuffed by his relatives for his pro-southern sentiments. (25) One of Huntley’s creditors, Joseph R. Broome, wrote to his sister, in a letter dated May 14, 1884,

Mr. Huntley is still absent – went to Syracuse, N.Y. to assist in closing up his father’s estate. If he doesn’t pay me pretty soon, I shall take charge of his plantation up the R.R. He claims that he will pay me, but I doubt his ability to do so. I trust that he may yet recover from his embarrassments.

On January 27, 1885, Broome wrote,

Huntley, who is mixed up in patent rights business, is there (Newark, New Jersey) now, and will remain there for months. I wish the fellow could make money.

Broome eventually foreclosed on the Tin Bridge farm. (26)

From his base in Newark, Huntley traveled about the country as a “patent man,” guiding inventors through the intricacies of obtaining and defending patents. The surge in industrialization in the second half of the nineteenth century resulted in massive disputes over patent rights. In exchange for a percentage of the profits, a patent man would handle all the paperwork, leaving the creator free to perfect his invention. The Gilded Age of the late 1870s and 1880s was a turbulent time economically. Some individuals made fortunes, while others lost everything. Huntley struggled along in the latter category. He was never able to duplicate the success he had with the roller skate patent. Concerned about the power wielded by big business, in 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act. The anti-big-business climate was reflected in the patent field as courts increasingly held patents invalid. An economic panic and subsequent depression in 1893 further hindered Huntley’s work. He must have realized his career in patents was a dead end. His long absences from home had estranged him from his family. His wife’s brothers were successful lawyers, industrialists, and journalists. His three children were embarked on successful careers. In comparison, he must have considered himself an utter failure. Overcome with depression, on a bleak December night in 1894, he drank a lethal dose of laudanum.

Notes

- DiRisio, Betty Hoover, A Confederate Among Us, Lawrence County Historical Society Facebook, September 12, 2021, https://www.lawrencechs.com/. Leland Madison Park Collection, MS-2019.09, Troup County Archives.

The Orlando Sentinel Star of May 26, 1975, published portions of a letter written in 1914, by Thomas McKee of New Castle, Pennsylvania, to Lemuel M. Park:

There lies here in Greenwood Cemetery a native son of Georgia who served during the war of 61 to 65, in a Georgia regiment. His name was Capt. W.H. Huntley of Atlanta, I believe. He died December 29, 1895 (sic) aged 70 years. Was buried and a tombstone erected by Post 100, Grand Army of the Republic, of this city, and his grave has been decorated ever since on Memorial Day. We would be glad to know if there are those in his homeplace or in the South who would like to know of his last resting place. If you are interested and will investigate, we would be very glad to get in touch with any friends who may wish to hear of him. He was a good citizen, but overtaken in his last days with misfortune, no fault of his.

- L. N. Benjamin published the proceedings of the raiders’ trials under the expansive title:

The St. Albans Raid; or, Investigation into the Charges Against Lieut. Bennett H. Young and Command, for Their Acts at St. Albans, Vermont, on the 19th October, 1864; Being a Complete and Authentic Report of All the Proceedings on the Demand of the United States for Their Extradition, Under the Ashburton Treaty, before Judge Coursol, J.S.P, and the Hon. Mr. Justice Smith, J.S.C., with the Arguments of Counsel and the Opinions of the Judges Revised by Themselves; Compiled by L.N. Benjamin, B.C.L., Montreal; Printed by John Lovell, St. Nicholas Street, 1865.

- Within hours of the St. Albans Raid, newspapers began to publish accounts of the action; some accurate, others laced with rumor and speculation. The same can be said of the myriad of publications that have appeared over the past century-and-a-half. Readers wishing to learn more about the raid and the raiders should consult, The St. Albans Raiders; An Investigation into the Identities of the Confederate Soldiers Who Attacked St. Albans, Vermont on October 19, 1864, by Daniel S. Rush and E. Gale Pewitt, published by Blue & Gray Education Society, 2008.

- Benjamin, L.N., The St Albans Raid, Montreal, 1865, 172

- Benjamin, 201

Defense attorneys introduced Huntley’s passport as Exhibit K. William Pope Wallace took the stand and identified himself as a staff officer for Brigadier General William Preston of Kentucky. He was in Canada escorting Preston’s family because the general had been appointed Confederate Minister to Mexico. Wallace testified that Huntley showed him the passport and other documents at Wilmington in February, 1864. He went on to state that he saw Huntley and Young in Halifax in May, 1864, and that Huntley stated he was going to Bermuda and Young was going to attempt to run the blockade.

- Rush, Daniel S. and Gale E. Pewitt, The St. Albans Raiders, Blue and Gray Education Society, 2008, 36-42.

In the spring of 1864, Jefferson Davis persuaded Jacob Thompson (1810-1885) and Clement C. Clay (1816-1887) to represent the Confederacy as commissioners in Canada. Operating out of Montreal, they financed and coordinated a network of Confederate agents. It appears that Clay was more enthusiastic than Thompson about Young’s plans, so the young lieutenant dealt primarily with him. As the war drew to a close, Federal authorities attempted to link Thompson and Clay to the Lincoln assassination. Thompson fled to England. Clay headed for Mexico. He stopped in Huntley’s hometown, LaGrange, Georgia, at the home of his friend and colleague, Benjamin H. Hill, and while there he learned from newspaper accounts that a reward was offered for his capture. Clay sought out Union General James H. Wilson at Macon, Georgia, and surrendered to him. Clay was imprisoned along with Jefferson Davis at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. He was never formally charged, and was released in 1867.

- Benjamin, 80. Defense exhibit N.

- Benjamin, 205, 208. Defense exhibit P.

Montrose Anderson Pallen, a Mississippi physician, was in Montreal directing efforts to smuggle medical supplies into the Confederacy. Pallen authenticated Clement Clay’s signature on the order directing Young to proceed with the St. Albans raid. He went on to testify that he saw both Swagar and Huntley in Mississippi earlier that summer, revealing that they traveled to Chicago via a southern route, rather than down from Canada.

- Muster Roll, Lieut. Young’s (5th) Company Retributors, C.S.A., Chicago, Illinois, August 31, 1864, National Archives and Records Administration, record group 109, microcopy 258, roll 76.

- Benjamin, 220.

Hotel keeper James L. Hogle testified that Huntley registered under the alias W.P. Jones.

- The intent of the raid has been debated since the day it occurred. Vermonters saw it as nothing more than a bank heist. The moniker “Retributors” and statements made by the raiders, even as they robbed the banks, indicates that they saw the mission as one of retaliation. They clearly intended to burn the town. It was impractical for twenty-odd raiders to confront hundreds of workers in an attempt to destroy the railroad shops, so the banks offered the next most tempting target. When U.S. officials portrayed the raiders as murderers and bank robbers, Clement Clay attempted to distance himself from the affair. He wrote to Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, and others, claiming that he only sanctioned robbing the banks in conjunction with destroying the town. From their Montreal jail, the raiders expressed disappointment in Clay, even though he had procured top Canadian lawyers for their defense. They turned to George N. Sanders. Sanders held no official status but was active among Confederate expatriates in Canada. His eldest son died in a Federal prison camp so he took great interest in the plan to liberate Camp Douglas. Some researchers have suggested that Sanders advocated robbing the banks as a means of funding additional mischief along the border. He publicly lamented the fact that the St Albans raid was limited in scope and warned that there was more to come.

- Benjamin, 61.

St. Albans residents identified raiders and testified as to their behavior during the raid.

- Rush, 76

The figure of $208,000 is widely accepted and has frequently been published as the sum taken from the St. Albans banks. Rush and Pewitt offer comprehensive analysis of losses alleged by the banks and totals confiscated from raiders.

- Rush, 50-51.

Young paid a sympathetic Vermont family to care for Higbee then hired a farm boy to guide him across the border into Canada. Young was captured the next day. According to legend, Higbee was smuggled across the border in a hay wagon and was never arrested.

- Benjamin, 1.

Huntley, alias William Hutchinson, was charged with “suspicion to commit a felony” and “remanded for examination.”

- Benjamin, 61.

- Benjamin, 91.

- Benjamin, 172.

- Rush, 26, 32, 59-61.

- Huntley Family Vertical File, Troup County Archives.

In a letter dated August 9, 1984, Huntley’s great granddaughter, Suzanne D. Levings, wrote to Frank Rankin, who was conducting research on the St. Albans raiders, “He married a girl from a prominent family but from what I gather from the different relatives a cussed ole gal!” Martha’s grandnephew, Arthur Park, wrote to his son, Leland, in 1965, “Capt. W.H. Huntley was Aunt Mat’s husband. After the war Capt. Huntley occupied himself variously as a buggy dealer, in sending a shipload of cedar to England, introduced roller skating into South America, and lived some years in European countries.”

- On July 4, 1867, Augusta, Georgia’s, Daily Constitutionalist published “O! I’m a Good Old Rebel.” The poem was later attributed to James Innes Randolph.

- In 1863, James Leonard Plimpton patented improvements to European designs which allowed skaters to pivot and brake. His real genius was exemplified in promoting skating as an activity in which young women and men could participate together.

- Johnson, Forrest Clark, III, Histories of LaGrange and Troup County, Georgia, 353, self-published,

- LaGrange Reporter, March 6, 1879, page 3.

- Huntley Family Vertical File, Troup County Archives.

- Broome Family Vertical File, Troup County Archives.