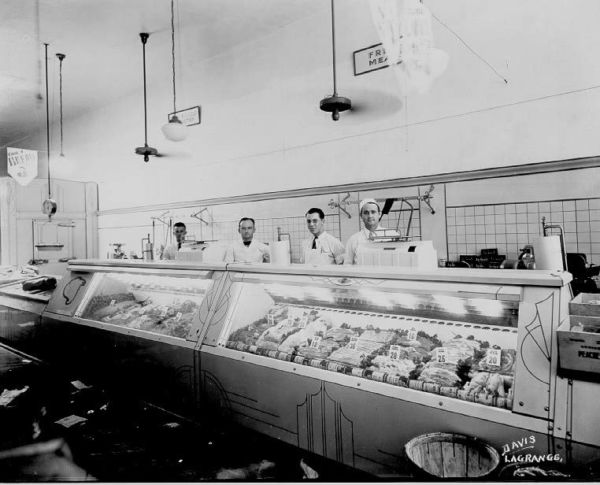

The meat counter at Rogers Store in LaGrange, c. 1940. TCA Collections

The history of the Food and Drug Administration is also the history of consumer protection as applied to food, drugs, and other products. The story began long before the letters, “F”, “D”, and “A” were household words. Scientists working to combat adulteration and ensure public safety were primarily involved in agricultural research to begin with, but they inevitably became involved with matters of food safety. Prior to government intervention, numerous unsafe products were marketed as safe. Conditions in the food and drug industries a century ago can barely be imagined today. Deceptive packaging was used to boost sales and fillers were used in products to make them go further. The materials used as fillers were often toxic or some form of adulteration. Milk was mixed with water and chemicals; arsenic and copper pesticides were used on plants; “lard” was made from cottonseed oil; radioactive water was even marketed as a health tonic. Use of chemical preservatives and toxic colors were virtually uncontrolled. As the American economy progressed from agricultural to industrial, it was suddenly necessary to provide a rapidly increasing city population with food from distant areas. Ice was the primary means of refrigeration and milk was unpasteurized; and opium, heroin, and morphine were sold without restrictions. Medicine men were popular with circuses, “wild west” performers, and minstrel shows. They would travel with the shows and sell their products. Hamlin’s Wizard Oil had one of the most popular big touring medicine shows. Patient cure-alls did not include the major ingredients and were sold to unsuspecting people. It was Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle, exposed unsanitary conditions in the Chicago beef stockyards. The work of fiction features stories of immigrant workers exploited for their labor and included details of the meatpacking industry. Following the release of Sinclair’s work, a crusade began to expand federal regulations and provide continuous inspection of all red meats. Although “seals of approval” generated from various sources were evident on food products during America’s “pure food movement” of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Bureau of Chemistry, FDA’s predecessor, acted to ensure that consumers were not misled by the word “guarantee” on early food labels. At the turn of the twentieth century, the term “pure” was reassuring to consumers, but the problem was that any product could call itself “pure.” The 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act was enacted at a time when America’s food supply was changing rapidly and were the first federal regulations of food and drugs.

Young boys standing in the Auto Dealership in Hogansville, where ice boxes were available for purchase. c. 1940, TCA Collections

Prior to this, there was no premarket approval needed for such products. In 1933, the newly renamed FDA recommended a complete revision of the 1906 Act and a five year legislative battle ensued. To show the need for a new law, the Food and Drug Administration created an exhibit for Congress featuring problem products the agency was unable to control under the 1906 Act. The collection of products featured deceptive foods, dangerous cosmetic ingredients, and worthless devices and medicines. A tragedy had to occur before legislation was passed to better protect Americans from false labeling, misleading ingredients, and harmful drug adulterants. After one hundred and seven people died from a poisonous ingredient in a product called Elixir Sulfanilamide, Congress passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act with new provisions in 1938. Drug manufacturers were required to provide scientific proof that new products could be safely used before putting them on the market, proof of fraud was no longer required to stop false claims for the usage of drugs, and countless food standards were established to promote honesty and fair dealing, all in the interest of consumers. World War II greatly expanded the FDA’s workload. Wartime stimulated the development of new “wonder drugs”, especially antibiotics, which were subject to FDA testing beginning with Penicillin in 1945. Most importantly, control was tightened over prescription drugs, new drugs, and investigational drugs. To establish a drug’s safety, it also had to be proven effective.

The Purdue family stands in the ice factory at Smith’s Mill in the Salem community, c. 1930, TCA Collections

The Drug Amendments of 1962 were passed unanimously by Congress and required adverse reactions to medications to be reported to the FDA. Preventing harm was the goal of any future amendments – gadgets and ‘quack machines’, which were previously allowed to be sold to the general public with promises to cure conditions, were taken off the market. The 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act authorized three kinds of food standards – identity, quality, and fill of container. By 1957, standards had been set for many varieties of foods such as chocolate, flour, cereals, bakery products, milk, cheese, juices, and eggs. Color additives were added to the list in 1960, requiring manufacturers to establish safety of colorings added to foods, drugs, cosmetics, and medical devices. By 1993, the nutrition label was required on most packaging – food nutrition information, like serving sizes, “low fat” and “light”, were standardized. Baby formula and commercially prepared baby foods were more tightly regulated with the passage of the Infant Formula Act of 1980, drafted specifically to insure that essential nutrients were included in foods for babies. Now, consumers are protected because so many people do things the right way. All across the country, workers in hospitals, drug stores, factories, and warehouses comply with food and drug safety laws. America has come a long way since times prior to federal regulation over food, drug, and cosmetic safety, but the work is a noble, continuous effort in the interest of public health. –Kaite Still