By Randall Allen

The genesis of this article goes back more than forty years. One Sunday afternoon my grandmother and I drove around Oak Grove Community, where she grew up. On Floyd Road (then called Pruitt Mill Road), we stopped at the site of the old Davidson grist mill on Turkey Creek. My great grandfather, Jake Pruitt, operated the mill during the first quarter of the twentieth century. As we walked around the old house place, examining the chimney piles and rock foundation, she pointed to a depression in the ground and said, “That’s our storm pit. Everybody had a storm pit back then. That’s where that boy hid ‘til Mama got so scared she told Papa he just had to leave.”

“What boy?” I asked.

“The Thompson boy. You know. The one they hung for killing the sheriff. After Mr. Bunk shot himself,

Papa had to go down there and clean it up. He said it was an awful mess.” Pointing again, this time to a clump of daffodils emerging from the broom sage, she abruptly changed the subject. “Look yonder. Do you think it would be stealing if I pulled some of Mama’s jonquils?” To my everlasting regret, I didn’t press her to divulge more about the story.

“The Shirey killing” has been a part of Troup County’s lore for at least three generations, but old-timers preferred to not discuss the sensitive subject. Perhaps now, with the passing of those directly involved in the event, the time has come to examine it more closely.

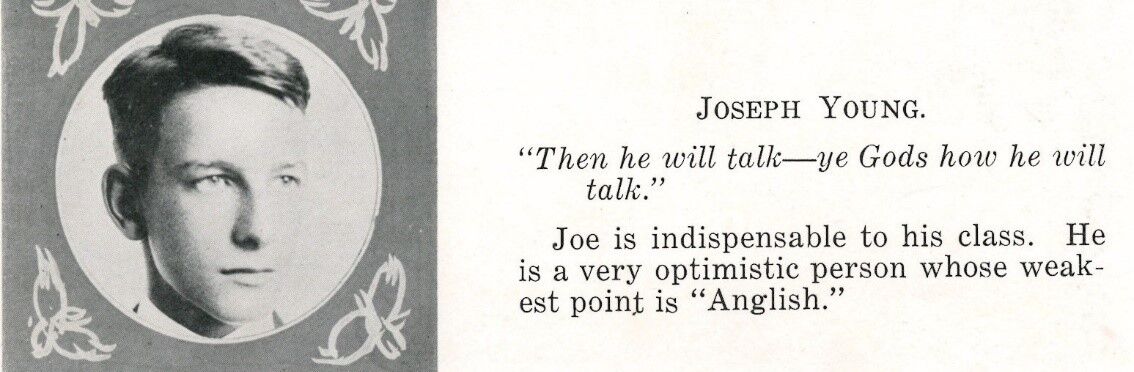

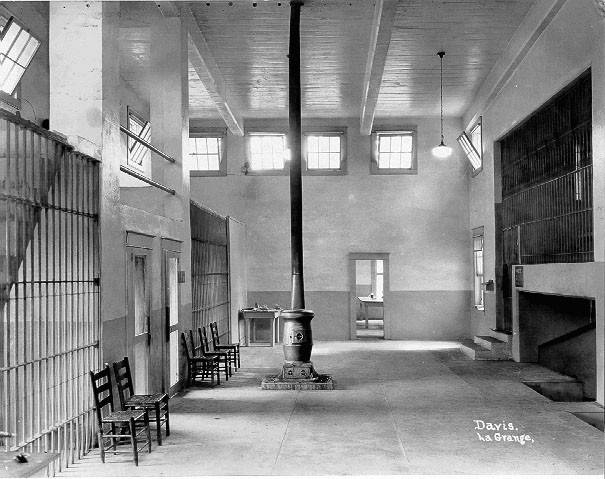

Shortly before 1:00 p.m. on July 26, 1918, John Marvin Thompson mounted the scaffold in the cellblock of the Troup County Jail on Hines Street in LaGrange. When Sheriff S.A. Smith asked the condemned twenty-three-year-old for his last words he stated, “I want all of you to know that I am dying innocent of what I am accused of. I have done things that I ought not to have done in my life, but God will forgive me for all I have ever done and He has promised to take me home.” He rambled momentarily about being mistreated in the whole affair, but stated that he held no grudges. “Tell all of my people good-bye for me, Papa, and tell Mama I love her.”

Byron Adolphus “Bunk” Thompson was among the small group of relatives, friends, and reporters assembled to witness the execution of his son. “I am sorry for you, John.” He responded. “I wish I could go with you.” Not long after his son’s hanging, the elder Thompson put the end of a shotgun barrel in his mouth and pulled the trigger. John’s mother, Emma O’Neal Thompson somehow persevered. She reared her nine remaining children on the farm, and died in 1965, a beloved and respected figure in the Oak Grove Community.

Sheriff Smith pulled the lever and young Thompson plunged into history and legend. A reporter noted that there was no struggle and never any sign of life after the drop. Seven minutes later, Dr. F.M. Ridley pronounced Thompson dead. He was buried in the Sturdivant Family Cemetery in Oak Grove.

Our attempt to reconstruct John Thompson’s story is based on oral history, court documents, and newspaper reports. In 1917 and 1918, rumor and hearsay surrounded the incident that led to Thompson’s execution. In the ensuing hundred years, the story has become meshed in speculation and legend. Any attempt to sort fact from myth is inhibited by a lack of documentation. There is no transcript for the trial proceedings. Our only record of witness statements comes from a summary of testimony in Thompson’s appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court. Issues of the LaGrange Reporter for that time period were lost in a 1921 fire, and the LaGrange Graphic, a weekly newspaper, offered more editorial content than factual reporting about the trial. Oral history, then, becomes an important source for information, but a conundrum arises because the scant written record is frequently at odds with local legend.

Our attempt to reconstruct John Thompson’s story is based on oral history, court documents, and newspaper reports. In 1917 and 1918, rumor and hearsay surrounded the incident that led to Thompson’s execution. In the ensuing hundred years, the story has become meshed in speculation and legend. Any attempt to sort fact from myth is inhibited by a lack of documentation. There is no transcript for the trial proceedings. Our only record of witness statements comes from a summary of testimony in Thompson’s appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court. Issues of the LaGrange Reporter for that time period were lost in a 1921 fire, and the LaGrange Graphic, a weekly newspaper, offered more editorial content than factual reporting about the trial. Oral history, then, becomes an important source for information, but a conundrum arises because the scant written record is frequently at odds with local legend.

Georgia enacted statewide prohibition in 1908, and predictably, the ensuing decade witnessed a surge in illicit liquor making. State and federal revenuers routinely targeted different areas of the state in a futile effort to curb the moonshiners. A pattern emerged. The risk of spending a few months on the chain gang seemed worth the monetary reward. The unlucky farmer-cum-bootlegger who was caught, usually just did his time and went right back to work when he got out. John Thompson chose a different path.

About noon on Monday, February 26, 1917, Troup County Sheriff William B. Shirey, his driver, Earnest Riley, and chief deputy, S.A. Smith, accompanied Federal Deputy Marshal J.A. Henderson to raid stills around the Oak Grove Community in the southern part of the county. Before day’s end the routine raid escalated into an epic tragedy for Troup County. John Thompson happened to be in LaGrange that day, and somehow learned that the sheriff was going to Oak Grove. He headed home knowing that his family’s illegal still was a likely target.

Thompson’s ancestors, the O’Neals and Sturdivants, had farmed the red land around Oak Grove since Troup County’s inception. They endured the Civil War and the upheaval of Reconstruction, and in the early twentieth century survived the onslaught of the boll weevil. Like many others, Bunk Thompson and his sons supplemented their income with an occasional run of moonshine. It was a tradition as old as our nation. George Washington’s greatest test as president was the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791 – 1794, in which farmers of western Pennsylvania refused to pay tax on whiskey they produced from their surplus grain.

Testimony summarized in Thompson’s appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court indicates that he raced ahead of the revenuers to warn fellow liquor makers of the impending raid. He attempted to recruit brothers Lewis and Lon Hart, and neighbor Walter Estridge, to join him in confronting the revenuers. The Harts declined, warning Thompson that it was too late to save his still. As Thompson and Estridge approached the still, around 2:30, they realized that the lawmen were busy destroying the operation. They had poured out about twenty barrels of malt beer, and Sheriff Shirey was about to take an axe to the vat of mash. John Thompson drew his pistol and began firing. Estridge followed suit. Sheriff Shirey was struck in the chest and died about thirty minutes later.

Shirey’s fellow officers testified that he was struck by the first shot, and that proved to be crucial. After the shooting Thompson and Estridge returned to Lewis Hart’s house where Thompson reportedly bragged, “If I didn’t do it, it wasn’t my fault.” He stated that he steadied his pistol against a pine tree for the first shot but then fired blindly as smoke obscured his vision. We will never know what motivated the young man to act so rashly. In later years, legend grew that there were many shooters that day. Byron Thompson’s subsequent suicide led to speculation that he actually fired the fatal shot, but Walter Estridge’s testimony indicates that he and John Thompson were the only shooters. Thompson’s bravado waned as the gravity of the situation sunk in. After he was arrested, he urged his companions to tell investigators that he had been working on his car at another location at the time of the shooting.

News of the shooting flashed around LaGrange and by that evening a posse was formed with the intention of heading to Oak Grove to apprehend the killers. Cooler heads prevailed and on Tuesday morning a force of State and Federal agents descended upon Troup County. Three additional stills were destroyed and eleven men arrested. Troup County was briefly in the national spotlight as both sides in the prohibition fight sought to capitalize on the incident. On February 28, 1917, Congressman James A. Galliran of Massachusetts, a staunch opponent of prohibition, read into the Congressional record an article from the Atlanta Constitution recounting the killing of Sheriff Shirey. He argued that there would always be demand for alcohol, and if it couldn’t be met legally, then outlaws would step in. He concluded, “Mr. Speaker, liquor has more enemies in public and more friends in private than any other substance the world has ever known. If some men in Congress shall have their way, the ashes of Sodom and Gomorrah would look like a bubbling spring in comparison with this land of ours when ‘bone dry’ becomes the real thing.”

Two local factions united in reaction to the Sheriff’s murder. Social reformers who were hotly engaged in the battle for national prohibition seized the opportunity to promote their cause. Powerful merchants and capitalists were ambivalent, if not outright opposed to prohibition, but they perceived the stigma of lawlessness as an impediment to their ambitions of urban development for LaGrange. Together, they clamored for quick justice.

The LaGrange Graphic of March 3, 1918, published notice of a public meeting.

To the Citizens of Troup County:

You are hereby notified to be present at the Superior Court room in LaGrange next Monday, March 5th, for the purpose of discussing ways and means for suppressing the illicit distilleries and unlawful sale of liquor in our county. The course of events of the past few days demand immediate action. It is up to the law abiding citizens to clean up Troup County. Meet at 11 o’clock a.m. in the courtroom. Let every district in the county send a large delegation.

A body of citizens

The headline for the same issue trumpeted: A TIME FOR ACTION

The time has come when the people of Troup County are aroused as never before. Our people have been sleeping over a volcano for the last several years, secure in the belief that our county was safe from the things which had made other sections of the country notorious for lawlessness. The volcano has erupted at last, and the law abiding people of LaGrange and Troup County stand appalled – horrified that lawlessness has endeavored to override the law, and plant its banner in defiance upon the hills of Troup County. When the information was heralded forth that Sheriff Shirey had been foully assassinated in the discharge of his official duties, our people stood aghast, dumbfounded and awestruck at the boldness of the deed. They could scarcely be made to realize that such a thing could have happened in Troup County. But it has happened and the citizens of our county stand face to face with a condition that must be blotted out at any cost. The life of ten thousand assassins is not worth the life of one W.B. Shirey. Wildcat stills and lawlessness must go if it takes measures beyond the pale of the law to drive them out. The life of no man is safe when the assassin can ply his trade as he is plying it today in Troup County. Wildcat stills are being operated in every section of the county, and those who operate them defy the law and threaten to murder an officer who attempts to interfere with their hellish business. It is time for action and we believe our people are thoroughly aroused to the situation.

No records from the investigation of the crime survive. We know only that eleven men were initially arrested, most charged with illegally manufacturing or selling liquor. John Thompson and Walter Estridge were jointly indicted for first degree murder. Thompson was tried first. Walter Estridge, as the prosecution’s chief witness, testified, “Both of us went to shooting. I shot kinder to the right of the way John shot … As well as I remember, I shot four times. It may have been I shot five times.” The Hart brothers and others testified regarding Thompson’s statement about steadying his pistol against a pine tree, and his story about working on his car. On May 3, 1917, after about six hours of deliberation, a Troup County jury returned a guilty verdict against John Thompson. Judge J.R. Terrell sentenced him to death. A few days later, a second jury convicted Walter Estridge of murder, but they recommended mercy, obligating Judge Terrell to sentence Estridge to life in prison.

No records from the investigation of the crime survive. We know only that eleven men were initially arrested, most charged with illegally manufacturing or selling liquor. John Thompson and Walter Estridge were jointly indicted for first degree murder. Thompson was tried first. Walter Estridge, as the prosecution’s chief witness, testified, “Both of us went to shooting. I shot kinder to the right of the way John shot … As well as I remember, I shot four times. It may have been I shot five times.” The Hart brothers and others testified regarding Thompson’s statement about steadying his pistol against a pine tree, and his story about working on his car. On May 3, 1917, after about six hours of deliberation, a Troup County jury returned a guilty verdict against John Thompson. Judge J.R. Terrell sentenced him to death. A few days later, a second jury convicted Walter Estridge of murder, but they recommended mercy, obligating Judge Terrell to sentence Estridge to life in prison.

Two days after his conviction, Troup County officials transferred Thompson to the Fulton County jail. They stated that the twenty-five-year-old Troup jail was in need of repair. Speculation then, and to this day, was that Troup County leaders had done such a good job of arousing public sentiment against Thompson that they could not guarantee his safety during the appeal process. Thompson remained in custody of Fulton County until March 8, 1918. The Atlanta Constitution published an account of Thompson’s transfer back to Troup County, stating that while in Fulton County he had been a model inmate. “He helped the deputies in their book-keeping and did many little duties around the jail with never a violation of the trust reposed in him.” The article concluded sarcastically, ”Inasmuch as the charge for feeding prisoners is only 40 cents in Troup, compared to 75 cents here, they did not feel inclined to leave him in Fulton County.” Thompson’s attorneys based his appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court on Judge J.R. Terrell’s denial of a motion for a change of venue, offering evidence that at least one juror stated that he would see Thompson hang in spite of a lack of evidence. The high court rejected the appeal, and on July 24, 1918, Governor Hugh Dorsey declined to commute the death sentence.

The day before his execution, Thompson penned this letter to Fulton County Sheriff James Lowry.

LaGrange, Ga. July 25, 1918

Dear Captain Lowry and all your deputies,

I can’t leave this old world without thanking you all one more time for all your kindness to me while I was in your care. I want to thank you all for what you have done for me since I have been away. God in Heaven will reward you all for everything you have done for me. So my time has come, and I have got to leave my loved ones and go to rest in Heaven, and my last word is that I am dying innocent of the crime, but it is God’s will. I am ready to go and I want to meet you all up there someday, and if any of you are ever on a jury again, don’t never find a man guilty on circumstantial evidence, for Captain, you see what it has done for me and God in Heaven knows I am innocent but I am helpless to prove it and these rich men and money have broke my back but one glorious thing, their money can’t keep me out of Heaven. Jesus Christ died on the cross to save sinners, so I am dying to save Walter Estridge and Lewis Hart. I wish you all a long and happy life, and you all remember me as your best friend. With love, I will remain you all sincere friend for I am going to Heaven.

Respectfully yours to all,

John Marvin Thompson