ATHOS MENABONI

(1895 – 1990)

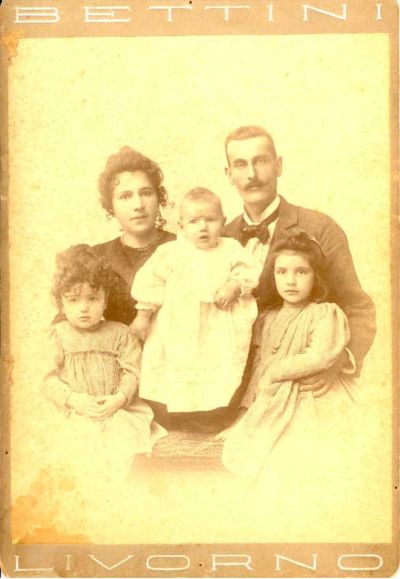

Jenny and Averardo Menaboni with Athos, Otto, and Margherita, 1898, TCA Collections

Athos Menaboni was born on October 20, 1895, to Averardo and Jenny Neri Menaboni in the Italian port city of Livorno. His maternal grandfather, Alessandro Neri, had been a military leader, with Giuseppe Garibaldi, in Italy’s unification movement. Menaboni’s father was a successful ship chandler (supplier). He also opened the first movie theater, and owned the first automobile in his hometown. As a result of his father’s bringing home exotic animals given to him by clients, young Athos developed the lifelong fascination with birds and other animals, which later became the subjects of his paintings. He also often rode his bicycle to nearby Pisa, where he admired the city’s art and architecture. At the age of nine, he began a formal study of art with private teachers, including Italian marine painter Ugo Manaresi, Belgian muralist Charles Doudelet, and Italian sculptor Pietro Gori. He later attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence.

Menaboni had no interest in his father’s business. Several years after World War I, during which he served as a sharpshooter and a pilot in Italy’s armed forces, he left home with a job on the American freighter, S.S. Colthraps (under the command of his father’s friend, Master John D. Hashagen), with layovers in Tunisia and the Madeira Islands along the way, and then finally landed in the United States in March 1921 (he eventually became an American citizen in 1939). After immigrating through the port of Norfolk, Virginia (his sponsor was Hashagen), he settled first in New York City, accepting minor commissions and taking a job for twelve dollars a week decorating candles. Three years later he went to Davis Islands, in Tampa, Florida, to become the art director, and designed printed advertisement for newspapers and promotional material for real estate developer David P. Davis (a relative of Hashagen, whom he had met while living in New York). He even designed the front elevation of an apartment building (Palace of Florence) there.

In 1927, after the Florida land boom had ended, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, and was employed by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company. Soon, though, he would be working on projects with Philip Shutze, one of the city’s foremost architects. During the next decade, Shutze hired him to do decorative painting at the Swan House, the home of Edward Inman, and in several other residences (the May Patterson Goodrum House, Spotswood Hall, and the Patterson-Carr House) as well as public buildings (The Temple and the Capital City Club). Menaboni also worked with other prominent architects, including Samuel Inman Cooper and Albert Howell. Other early commissions included restoration work on Atlanta’s Cyclorama, decorative painting of the lobby ceiling in the Rhodes- Haverty Building, and murals in the chapel at Saint Joseph’s Hospital. He designed and painted the Egyptian-themed art in the Al Sihah Shrine Temple in Macon, Georgia, and painted murals for a bank building (also in Macon) as well as in the home of tobacco magnate Richard J. Reynolds on Sapelo Island (another Shutze project). He even taught art lessons at the short-lived Atlanta Academy of Fine and Applied Arts. During this period, he also earned money painting landscapes and seascapes.

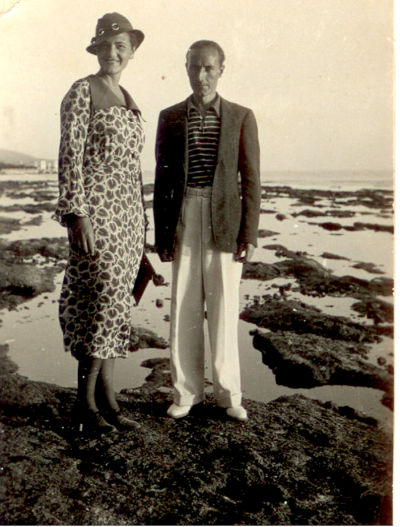

Sara and Athos Menaboni, 1928, TCA Collections

For the first year in Atlanta, Menaboni lived in a downtown Peachtree Street boarding house owned by an uncle of his future wife. It was here that, one month after moving in, he met Sara Regina Arnold, of Rome, Georgia, whom he married on August 14, 1928. After honeymooning two months in Italy, they rented a small apartment, first on Tenth and later on Eleventh Street. In 1939, they bought six acres in Dunwoody, an Atlanta suburb, where, in 1942, they built a house. The address was 1111 Cook Road, later renamed Crest Valley Drive (they had rented a house on nearby Jett Road before their home was constructed). They named their property Valle Ombrosa (Shady Valley) after Vallombrosa, a town southeast of Florence, Italy, which was Menaboni’s favorite holiday destination during his boyhood summers. Their little estate became a bird sanctuary, complete with its own aviary, a pond, and it also included a greenhouse for the cultivation of Menaboni’s bonsai. Husband and wife lived and worked there for the rest of their lives.

In 1937, between jobs, Menaboni began experimenting with paint pigments, and returned to his early childhood interest in birds. When he painted a pair of cardinals for a wall in his own living room, an interior designer and close friend, Molly Whitehead Aeck, noticed the painting and insisted that she be allowed to purchase it for a client. The resulting sale marked the beginning of a shift in Athos Menaboni’s career, and from then on, he steadily refined aspects of the art for which he is now famous – naturalistic oil paintings of birds. He developed a technique he referred to as his “undercoat method,” which used turpentine to thin the oil in order to paint in layers on paper that gave the feathers translucency, detail, and depth. Admirers continue to mistake these paintings for watercolors.

Sara Menaboni’s sending, in 1938, a portfolio of his bird paintings to her sister-in-law, Augusta “Tommy” Arnold, in New Jersey, led almost immediately to major exhibitions in nearby New York City at the American Museum of Natural History and the National Audubon Society. Throughout the remainder of the decade, she worked tirelessly to get the artist’s name and art before the public in New England, even traveling to Boston, Newport, and beyond, arranging exhibitions. The show at Kennedy and Company (later known as Kennedy Galleries) led in turn to Menaboni’s long association with Robert W. Woodruff of The Coca-Cola Company, for it was there in New York that some of Woodruff’s close associates noticed and purchased the painting Doves in Longleaf Pine for the Woodruffs. It reminded them of a scene at Ichauway Plantation, the Woodruffs’ beloved Baker County, Georgia, retreat. Mrs. Woodruff decided to use an image of the art on their 1941 Christmas card. It became a tradition, with a different Menaboni bird painting each year until 1984 (Mr. Woodruff died in March 1985). Atlanta’s Emory University and the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation, along with the Troup County Archives in LaGrange, Georgia, all hold a complete set of the forty-four card series, sometimes described by collectors and enthusiasts, including the Smithsonian Institution, as one of the nation’s finest. Framed reproductions are displayed at Callaway Gardens in Pine Mountain, Georgia.

Sara and Athos Menaboni, c. 1942, TCA Collections

From the late 1930s on, Menaboni’s range of media broadened. During this time, he rendered countless landscapes, seascapes, botanicals, nature studies, and what might be termed surreal fantasies on a variety of materials, including silk, wood, Masonite, cork, and paper. In 1939, he created fifteen mirrors, done in reverse painting on glass (before it was silvered), for a windowless dining room at Atlanta’s Capital City Club. Then, between 1951 and 1969, he was able to return to an interest from earlier in his career when Mills B. Lane Jr., at that time president of The Citizens and Southern National Bank, commissioned him to paint murals in bank buildings in Atlanta and Albany, Georgia, and to create an eggshell mosaic for the branch in Decatur, Georgia. He did magazine work as well. For example, he painted sixteen covers for The Progressive Farmer and two for Sports Illustrated.

Athos Menaboni, c. 1948, TCA Collections

Since 1942, Menaboni’s work has been made even more widely available through prints and lithographs produced by, among other institutions and companies, the National Audubon Society. In 1953 and 1959, respectively, his birds appeared in an ad for the Prudential Insurance Company, and on a calendar produced by The Coca-Cola Company.

In 1950, Sara and Athos Menaboni published Menaboni’s Birds. His paintings illustrated the text written by his wife, and the volume was voted one of the “Fifty Best Books of the Year” by the American Institute of Graphic Arts. It was reissued in 1984 using the original text with thirty-one new full-color reproductions. Menaboni’s art also illustrates several other authors’ books, including Never the Nightingale by Daniel Whitehead Hicky (a Georgia poet) as well as the article on birds in The World Book Encyclopedia.

It was also in 1950 that Time declared Menaboni the heir of James Audubon, an apt designation, given the fact he would eventually paint over one hundred sixty different species of birds. This magazine’s recognition was just one of many he would receive. During his career in Atlanta, which spanned sixty-three years, he welcomed awards from the American Graphic Society, the Georgia Writers Association, the New York Art Directors Club, the American Institute of Graphic Arts, the Atlanta Beautiful Commission, the Capital City Club, the American Institute of Architects, the Italian Cultural Society, the Garden Club of Georgia, and the Office of the Governor of Georgia (the Governor’s Award in Visual Arts).

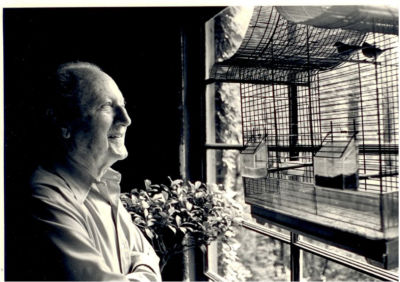

Athos Menaboni, 1987, TCA Collections

In 1990, Athos Menaboni suffered a stroke, and died two months later (on July 18) at age ninety-four. His body was donated to the Emory University School of Medicine. A memorial service was held at the Ida Cason Callaway Memorial Chapel at Callaway Gardens on July 22, and the eulogy was delivered by Elizabeth Carlock Harris, Georgia’s first lady. Sara died three years later on August 10, 1993. Their remains were interred at Arlington Memorial Park in Sandy Springs, Georgia. The Menabonis left their estates to Callaway Gardens, where his easels and paintings from his personal collection, including the Callaway collection, are on permanent exhibition in the Athos Menaboni Wing in the Virginia Hand Callaway Discovery Center.

Menaboni’s works have been exhibited in many galleries and in art and natural history museums across the United States. They include the Kennedy Galleries, the Columbia Museum of Art, the Pensacola Arts Center, the Marietta Cobb Museum of Art, the Albany Museum of Art, The Martha Berry Museum at Berry College, Emory University, the Vose Gallery, the St. Louis Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art, the Atlanta History Center, the Seattle Art Museum, the Santa Barbara Museum, the Detroit Art Museum, the Stark Museum of Art, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Booth Western Art Museum, The Bascom: A Center for the Visual Arts, Madison-Morgan Cultural Center, and the Jekyll Island Arts Association.

In 2007, Russell Clayton, a retired Marietta, Georgia, educator and a friend of Sara and Athos Menaboni, donated Menaboni art and an extensive archive collection to Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia. The art collection includes paintings, drawings, three-dimensional works, prints, and lithographs. Two generous grants, totaling $1.3 million, from the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation sponsored the Don Russell Clayton Gallery, located in the Zuckerman Museum of Art, which was used to mount exhibitions that honored Menaboni’s life and career. The Athos Menaboni Permanent Art Collection continues to grow with additional works given by Clayton and other donors.

In 2013, Clayton transferred the archive collection from KSU to the Troup County Archives. The TCA also houses material from the Menabonis’ estates donated by Callaway Gardens. Archive collections can also be found at the University of Georgia and Emory University, and his art is included in the permanent collections of many museums and institutions.

At Kennesaw State University, the Athos Menaboni Gallery will open soon. Its funding came from a $1.1 million bequest from Emily Bourne Grigsby, a friend of the artist and Clayton, and will serve as a permanent venue for exhibitions of art only by Menaboni.

Exhibitions continue to be planned and mounted. The art of Athos Menaboni lives on.